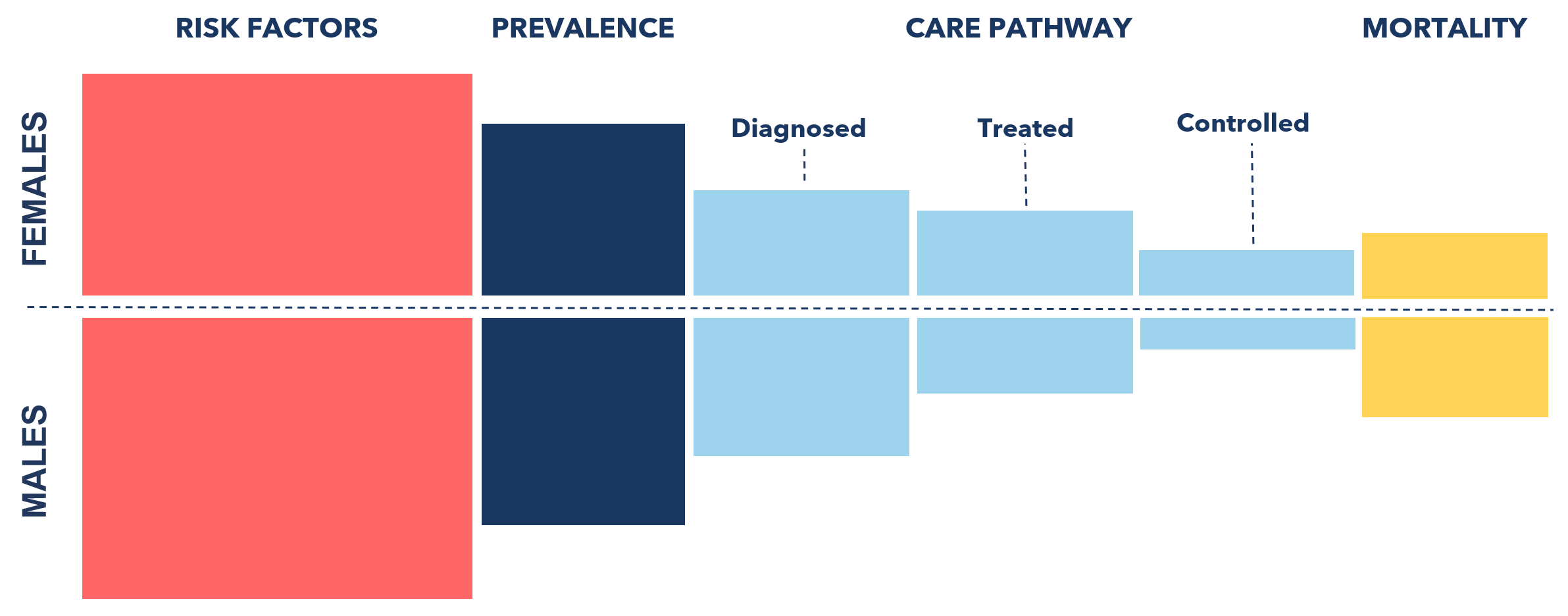

EVIDENCE ALONG THE PATHWAY: WHAT GENDER-RESPONSIVE INTERVENTIONS WORK?

What do we know so far about interventions that take gender into account can help people with, or at risk of, hypertension, HIV, or diabetes? And how might such interventions contribute to reducing gender inequalities along the health pathway?

With a more gender-responsive approach to health, what could be achieved in reducing risks, strengthening prevention and making health services more accessible to all?

We’ve gathered insights from studies, reviews and health programming that have delivered results by taking gender norms and disparities into account.

And already we’re seeing how targeted, gendered interventions are, for example, reducing cases of hypertension. But there’s much more we can do.

By piecing together all the data we have — and collaborating to build an ever-clearer picture – we can make sure that what we do reaches more people and delivers better health for all.

Literature on gender-responsive interventions along the pathway

References

1. Robertson, C., Archibald, D., Avenell, A., Douglas, F., Hoddinott, P., van Teijlingen, E., Boyers, D., Stewart, F., Boachie, C., Fioratou, E., Wilkins, D., Street, T., Carroll, P., & Fowler, C. (2014). Systematic reviews of and integrated report on the quantitative, qualitative and economic evidence base for the management of obesity in men. Health Technology Assessment, 18(35), v–vi, xxiii–xxix, 1–424. https://doi.org/10.3310/hta18350

2. VicHealth. (2017). Young men urged to stop stalling and quit [Press release]. VicHealth. https://www.vichealth.vic.gov.au/media-and-resources/media-releases/young-men-urged-to-stop-stalling-and-quit

3. (a) Green, C. A., Polen, M. R., Dickinson, D. M., Lynch, F. L., & Bennett, M. D. (2002). Gender differences in predictors of initiation, retention, and completion in an HMO-based substance abuse treatment program. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 23(4), 285–295. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0740-5472(02)00278-7

(b) Greenfield, S. F., Brooks, A. J., Gordon, S. M., Green, C. A., Kropp, F., McHugh, R. K., Lincoln, M., Hien, D., & Miele, G. M. (2007). Substance abuse treatment entry, retention, and outcome in women: A review of the literature. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 86(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.05.012

4. (a) Brady, T. M., & Ashley, O. S. (2005). Women in substance abuse treatment: Results from the Alcohol and Drug Services Study (ADSS). U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Office of Applied Studies. https://www.ojp.gov/ncjrs/virtual-library/abstracts/women-substance-abuse-treatment-results-alcohol-and-drug-services

(b) Greenfield, S. F., Brooks, A. J., Gordon, S. M., Green, C. A., Kropp, F., McHugh, R. K., Lincoln, M., Hien, D., & Miele, G. M. (2007). Substance abuse treatment entry, retention, and outcome in women: A review of the literature. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 86(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.05.012

5. McCrady, B. S., Epstein, E. E., & Fokas, K. F. (2020). Treatment interventions for women with alcohol use disorder. Alcohol Research: Current Reviews, 40(2), 08. https://doi.org/10.35946/arcr.v40.2.08

Literature on gender-responsive interventions along the pathway

References

1. Gay J, Hardee K, Croce- Galis M, Kowalski S. (2010). What works for women and girls: Evidence for HIV and AIDS interventions. New York: Open Society Institute. https://www.opensocietyfoundations.org/uploads/546b3075-a617-4119-884c-21221544176d/what-works-for-women-and-girls-20100811_0.pdf

2. Nglazi MD, van Schaik N, Kranzer K, Lawn SD, Wood R,Bekker L-G. An incentivized HIV counseling and testing program targeting hard-to-reach unemployed men in Cape Town, South Africa. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2012; 59: e28–34. DOI: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31824445f0

3. Toska E, Gittings L, Hodes R, et al. Resourcing resilience: social protection for HIV prevention amongst children and adolescents in eastern and southern Africa. Afr J AIDS Res 2016; 15: 123–40. DOI: 10.2989/16085906.2016.1194299

4. Sharma M, Ying R, Tarr G, Barnabas R. Systematic review and meta-analysis of community and facility-based HIV testing to address linkage to care gaps in sub-Saharan Africa. Nature 2015; 528: S77–85. DOI: 10.1038/nature16044

5. Yeganeh N, Simon M, Mindry D, et al. Barriers and facilitators for men to attend prenatal care and obtain HIV voluntary counseling and testing in Brazil. PLoS One 2017; 12: e0175505. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0175505

6. Cherutich P, Bunnell R, Mermin J. HIV testing: current practice and future directions. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep 2013; 10: 134–41.

7. Colvin C. J. (2019). Strategies for engaging men in HIV services. The lancet. HIV, 6(3), e191–e200. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-3018(19)30032-3

8. Sevelius JM, Dilworth SE, Reback CJ, Chakravarty D, Castro D, Johnson MO, McCree B, Jackson A, Mata RP, Neilands TB. Randomized Controlled Trial of Healthy Divas: A Gender-Affirming, Peer-Delivered Intervention to Improve HIV Care Engagement Among Transgender Women Living With HIV. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2022 Aug 15;90(5):508-516. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000003014. Epub 2022 Mar 5. PMID: 35502891; PMCID: PMC9259040. DOI: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000003014

Literature on gender-responsive interventions along the pathway

References

1. Harreiter J, Kautzky-Willer A. Sex and Gender Differences in Prevention of Type 2 Diabetes. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2018 May 4;9:220. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2018.00220. PMID: 29780358; PMCID: PMC5945816. DOI: 10.3389/fendo.2018.00220

2. Robertson C, Archibald D, Avenell A, Douglas F, Hoddinott P, van Teijlingen E, Boyers D, Stewart F, Boachie C, Fioratou E, Wilkins D, Street T, Carroll P, Fowler C. Systematic reviews of and integrated report on the quantitative, qualitative and economic evidence base for the management of obesity in men. Health Technol Assess. 2014 May;18(35):v-vi, xxiii-xxix, 1-424. doi: 10.3310/hta18350. PMID: 24857516; PMCID: PMC4781190. DOI: 10.3310/hta18350

3. Hunt K, Wyke S, Gray CM, Anderson AS, Brady A, Bunn C, et al. A gender-sensitised weight loss and healthy living programme for overweight and obese men delivered by Scottish Premier League football clubs (FFIT): a pragmatic randomised controlled trial. Lancet (2014) 383(9924):1211–21. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62420-4. DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62420-4

4. Quit Victoria. (2017, April 10). Young men urged to stop stalling and quit [Media release (https://www.cancervic.org.au/about/media-releases/2017-media-releases/april-2017/young-men-urged-to-stop-stalling-and-quit.html.)

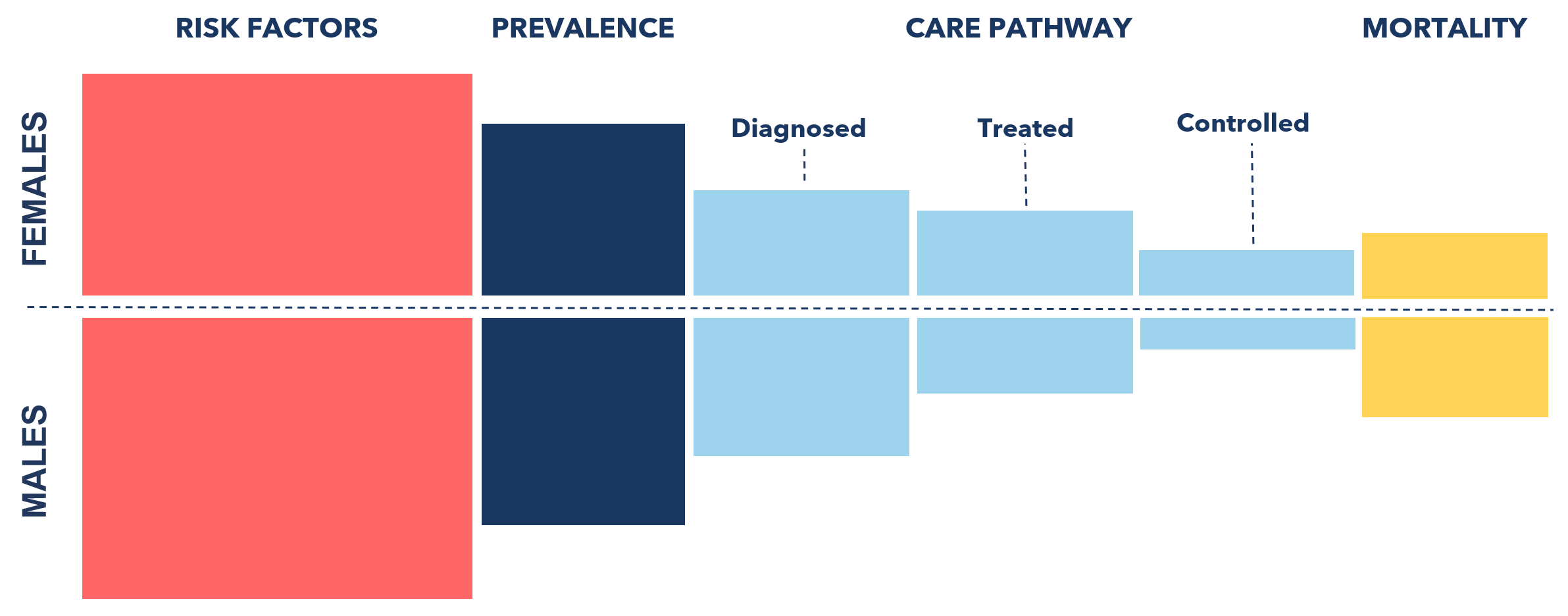

Do you have insights to add?

We want to collaborate with health data communities, health ministries and public health experts to collate more evidence, build more pathway visualisations and inform more responsive health policies and interventions.

We’d love you to join the conversation.